Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows is a glorious story of country- and river-side idyll. Over the last hundred years or so, the tale of Ratty, Mole, Badger and the notorious Mr. Toad has been adapted, reworked and revamped into numerous plays, musicals, films and cartoons. But I have never seen or heard of the particular twist that was woven into this production by the Yvonne Arnaud Youth Theatre.

There were two sides to this story. The first was true to the original tale and tracked the famous folk of the riverbank through their crusade to save Toad from himself. Ratty, cultured and kind, together with the timid and earnest Mole, enlisted the help of wise, gruff Badger to prevent Toad from pursuing his latest obsession with the motor car. Toad crashes several cars before his friends put him under house-arrest. He escapes, steals and crashes another vehicle, escapes again from his subsequent imprisonment and, with the help of his friends, finally liberates Toad Hall from the unruly mob of weasels, stoats and ferrets who had taken it over in his absence. Whew!

The parallel story running alongside, introduced an uncomfortable twist to this familiar tale. Here, the ‘unruly mob’ representing the creatures of the Wild Wood, were servants at Toad Hall who banded together to liberate themselves from the tyranny of the ruling class. They were instructed by their leader to call each other ‘brother’ and plotted a revolution to overthrow the spoilt and conceited Toad, take over Toad Hall and live together as equals, sharing the wealth between all.

They had planned and instigated Toad’s demise: from fuelling his car-obsession, to giving him the keys to escape from his house arrest and handing him the starter handle to the magistrate’s car that they had left at the end of his drive. They laid their plans carefully, allowing the flaws in Toad’s character to lead him down the road to self-destruction, in order that they could be free. It was with mixed feelings then that we watched the riverbank bourgeoisie quash the revolution of the Wild Wood proletariat.

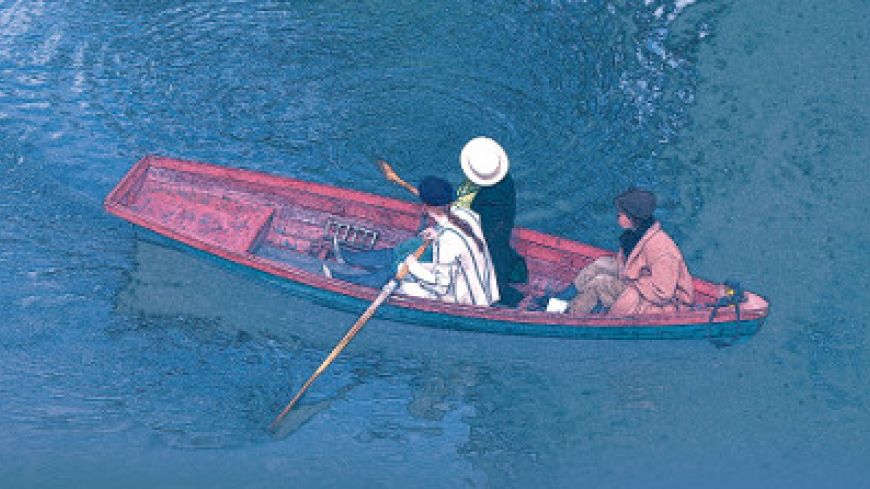

There was lots of singing, humour and creative staging in this unusual adaptation, all performed with the energy and enthusiasm of youth. The twist in the tale carried the germ of fruitful potential development, but ultimately contained the seeds of its own destruction. The pastoral, gentle narrative of ‘messing about in boats’ was injected with the politics of something altogether more serious which, in the end, poop-pooped all over the original story.

Run ended