David Greig’s adaptation of Strindberg’s Creditors delves into the turbulent and murky waters of the human mind to deliver a savage expose of love and revenge.

It‘s an oft-repeated cliché that relationships are all about the give and take, and, arguably, in a healthy relationship no-one’s actually counting. But what if someone forces you to address the balance sheet, questioning your version of reality with such malevolent manipulation that all the certainties on which your life is built evaporate, leaving you gasping for air?

In Creditors, Tekla’s ex-husband Gustav, scorned and humiliated when she left him for the younger Adolph, takes his long-awaited, bitter revenge. In three intimate and chilling scenes, the relationship between Tekla and Adoph is slowly eviscerated, along with Adolph’s grip on life itself.

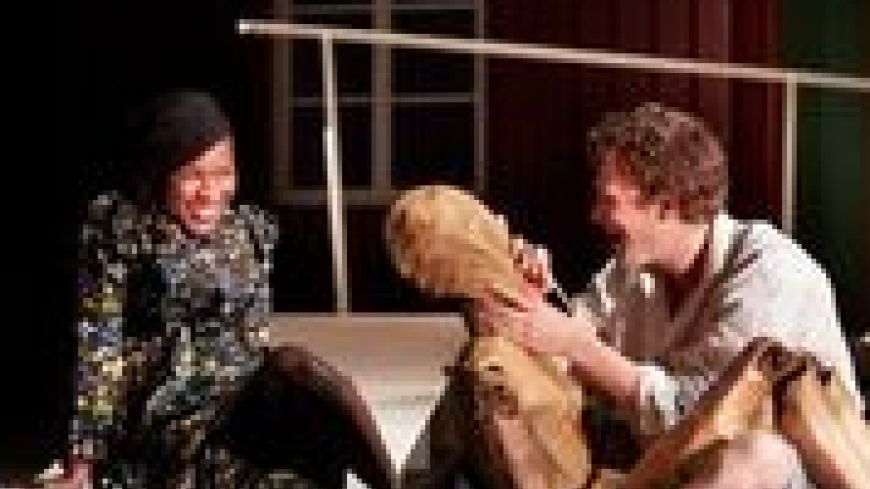

Stuart McQuarrie’s Gustav is a reserved, calculating manipulator, playing with Edward Franklin’s open and naïve Adolph like a puppet. As they both relax outside a Scandinavian holiday chalet, all begins airily and innocently enough. But Gustav, who hides his identity from Adolph, begins to gently sew seeds of doubt, layering up reinterpretations of Adolph’s cherished relationship with Tekla, until this tilting and tipping of Adolph’s world appears to have a vertiginous effect.

The focus then shifts as Adolph, with Gustav eavesdropping nearby, confronts Adura Onashile’s confident, sensual, Tekla, just as Gustav has instructed. Tekla’s confusion and Adolph’s desperate frustration build, bringing with it a sense of menace and inevitable foreboding. Finally, Gustav and Tekla meet inside the chalet, where their interaction is filmed and projected onto a screen outside. This clever use of a close-up camera turns this scene into a black and white movie, amplifying the sense of claustrophobic intensity as we, along with Adolph, eavesdrop outside the door.

It’s a chilling play that questions not only the nature of love but of reality itself. In Greig’s, as in Strindberg’s, script the (then) very modern term of ‘free-thinker’ is bandied about, giving voice to a predicament that resonates today: in a world without God the truth is up for grabs, and in such a climate of uncertainty clever manipulators can prey on doubts and fears. Ultimately, those who speak with the loudest voice (often in caps) get their truth heard and thus make the world. Brutal and unnerving.

Runs until 12th May