Imagine a darker version of Walk the Line, perhaps as directed by David Lynch, and you begin to get an idea of what to expect from this imaginary biopic.

Its

subject, Jesco White is from a similar kind of southern white rural

background to Johnny Cash, but less well known and far more troubled in

terms of drugs, drink, depression, and the devil alike.

White’s

youth was spent looking for whatever kicks he could find, beginning

with self-asphyxiation around the age of six before quickly moving onto

“huffing” lighter fluid and petrol, drinking whatever he could lay his

hands on, injecting crystal meth, and developing a penchant for

tattooing and wounding himself.

As far as his father and

mother were concerned, Jesco had the devil in him. Unfortunately, Jesco

himself believed this – in his environment, full of fire-and-brimstone

preachers it would be hard not to – and lived up/down to it.

His

sole release was another D, dance, specifically the distinctive form of

Appalachian mountain dancing or clogging of which his father, D Ray,

was a leading exponent.

Unfortunately, Jesco could never quite

keep his devils at bay and wound up in a juvenile detention centre,

which he went in and out of for the rest of his adolescence, before

being sent to the state mental hospital. The constant on each occasion

was a lack of effective therapeutic interventions, the sense that he

and the other inmates/patients – the label really made no difference –

were individuals who did not matter.

Eventually Jesco was

released, albeit into a world of trouble. Most significantly his father

had been murdered whilst he was institutionalised.

This fuelled

both the positive aspects of Jesco’s being, in his desire to keep his

father’s dancing legacy alive, and the negative, in his “eye for an

eye” understanding of the Bible.

The conflict between the good

and the bad Jesco, or the straight and the intoxicated, is at the core

of the remainder of the story, clouding his relationship with his older

girlfriend Priscilla and leading inexorably to tragedy.

White Lightnin’ is well directed. Though there are some moments where it feels like

technique for the sake of it, most of the tricks within helmer Dominic

Murphy’s bag contribute to the overall effect in a more poetic

form-is-content way: the black screens between scenes and their

suggestion that an indeterminate amount of time has passed, either

subjectively or objectively, for Jesco; the bleached out, processed

visuals the sickness and poverty of his (un)natural environment.

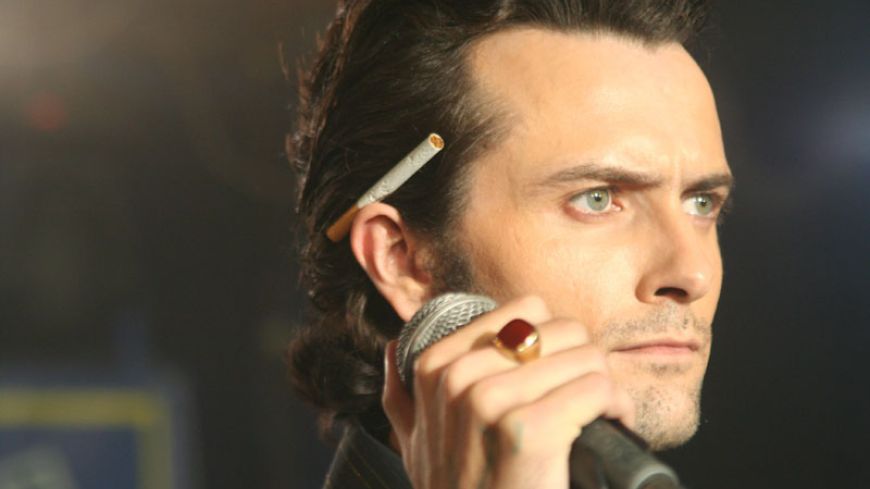

It

is also nicely acted. As Jesco, Edward Hogg delivering a bold, primal

performance. As Priscilla, Carrie Fisher bravely takes on the kind of

older woman role that many performers more concerned with their image

would likely have declined.

The main problem I had with the film was thus its writing, its treatment of the facts.

On the positive side, White Lightnin’ did encourage me to find out more about Jesco White.

It is also true that it is a highly subjective portrait, with many

scenes which deliberately confuse real and the imagined situations and

experiences.

But – and it is a big but – screenwriters Eddy

Moretti and Shane Smith play rather too fast and loose with things on

occasion. Most notably, the most significant moment in Jesco’s life,

the murder of his father, happened when he was in his late 20s, rather

than his teens as presented here.

Indeed in general the

film-makers seem more comfortable creating a sense of place than they

do time. Perhaps the intention is to suggest that nothing really

changes in this part of the USA – we may, after all, wonder why D Ray’s

success as a dancer didn’t lift his family out of poverty – but a more

1950s or 1960s rather than 1990s feel to the details of trucks,

motorcycles and tattoo designs might have helped cement this idea.

If

the film’s dark subject matter means it needs to be approached with

some caution, it’s also important to emphasise it’s not as bad as it

could be. For that, interested parties are recommended to check out

Todd Phillips documentary about outlaw rocker G G Allin, a

self-destructive damage case whose train-wreck of a life makes even

White look lucky and well-adjusted.