The title Giallo refers, generically, to a distinctive kind of Italian

horror-thriller film, of which writer-director Dario Argento has been a

leading exponent since his 1970 debut The Bird with the Crystal

Plumage.

As such, it’s a very self-referential title, akin to

Pulp Fiction, and one which is also indicative of the film’s nature,

that it is more for his fan-base in Italy and internationally than an

attempt to reach a new audience.

The big question, even as far

as this audience is concerned, is whether the film can live up to fan

expectation. Or, insofar as Argento’s stock is currently at a low level

in the wake of a string of poorly received films – 2004’s The Card

Player, 2005’s Do You Like Hitchcock and 2007’s The Third Mother –

whether it might actually surpass them for those sufficiently dedicated

to find out.

Amongst mainstream critics, meanwhile, Argento’s

reputation, such as it is, is that of a virtuoso stylist who is not

particularly good with narrative and characterisation, and whose work

is often marred by its gratuitous violence and misogyny.

While

he has tried to address these criticisms, the results as seen in the

likes of 1993’s Trauma and 1996’s The Stendhal Syndrome, have ended up

pleasing fewer fans whilst still failing to curry favour with the

critics.

The one exception, at least as fans were concerned, was

2001’s Sleepless, a film widely perceived as a return to form,

precisely because it presented a kind of retrospective ‘greatest hits’

package that looked back to Argento’s 1970s and early 1980s work. It

also came in the wake of his idiosyncratic 1998 adaptation of The

Phantom of the Opera, a film which few have anything positive to say

about.

It’s at this point that I must declare my own position: I

think that each and every one of Argento’s films has something to make

them worthwhile, and that Sleepless is over-rated compared to Trauma,

The Stendhal Syndrome and The Card Player. I also think that, if taken

as an intentional parody – always an awkward critical position to take,

admittedly – The Phantom of the Opera actually works.

It is

also in this way that I would argue Giallo’s apparent weak points may

be taken as strengths, such that we can laugh with the film’s more

awkward moments rather than at them.

Before accentuating the

possible negatives, however, I would like first to address the

positives. Like Sleepless, Giallo is a film that breaks little new

ground. But whereas its predecessor made a somewhat selective survey of

the high points of Argento’s past films, Giallo looks all around.

Thus,

for example, while we get a nightmarish yet naturalistic re-imagining

of Suspiria and Inferno’s taxi rides – the maniac here is a taxi driver

– we also also have an exciting rooftop chase finale that recalls the

less well regarded Cat o’ Nine Tails.

Argento also continues

to explore his emergent interest in Japanese culture, as previously

seen in The Third Mother’s Gothic Lolita / J-horror styled witch

follower of the mother. Giallo’s maniac, himself given the name

Giallo for a meaningful diegetic reason, draws inspiration from violent

hentai manga and subjects his victims to sadistic tortures that

wouldn’t be out of place in Takashi Miike’s Audition. Disconcertingly

– but ultimately tellingly, via past traumas, involving their

respective mothers, that define both men’s present situations – his

police nemesis also buys a volume of Japanese pornographer /

photographer Araki’s work.

Elsewhere we may note the name of

the overarching production company, Hannibal Films, as in Lektor; the

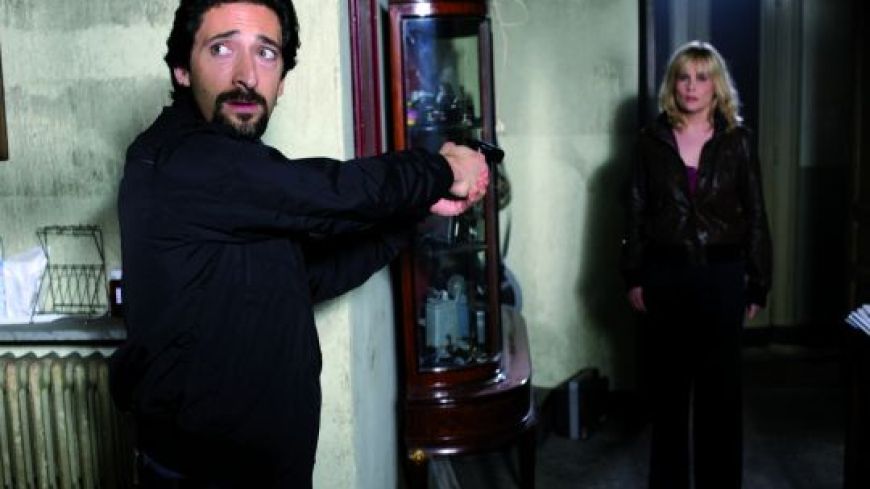

presence of Polanski veterans Adrian Brody and Emanuelle Seigner, also

of course Mrs Polanski; and, in a more throwaway manner, the returning

the favour presence of a poster for Juno.

The Thomas Harris

reference serves to further highlight the Manhunter-esque relationship

between cop and maniac and to explain away the rather unusual position

the former occupies within the Turin police force.

The plot

can be summarised as follows: Giallo’s modus operandi is to kidnap

beautiful young women whose absence will not immediately be noticed.

One such victim is Celine, a young fashion model; giallo fans will

immediately notice the form’s long fascination with the world of

glamour, dating all the way back to Mario Bava’s foundational 1964

entry Blood and Black Lace. Unfortunately for Giallo, and perhaps

fortunately for Celine, her air-hostess sister Linda (Seigner) has just

arrived in town to pay a visit. Concerned by Celine’s failure to show

up for their rendezvous, Linda goes to the police station to file a

missing person’s report and is there sent to see Inspector Enzo Avolfi

(Brody) in the bowels of the building. He soon realises the “pattern

killer” he is hunting has struck again and they embark on a desperate

race against time to save Celine…

It provides a solid framework for plenty of classic Argento images, suspense, shocks and splatter.

In

the case of the violence, however, it’s also important to note that as

much is suggested as shown. Besides helping answer those who would

argue Argento’s violence is only gratuitous, it’s an approach which

proves beneficial insofar as it showcases what special effects man

Sergio Stivaletti can do rather than what he perhaps might struggle at,

namely convincing in-camera facial mutilation effects, and the desire

of a portion of the audience to see such images.

The other thing

Giallo has is a lot of humour. Humour is, of course, not alien to the

horror film. But it is also something that is difficult to do well, as

criticism of the comic relief moments in Argento’s films testifies. In

Giallo, I think the key thing is that Brody, whose deadpan delivery of

key lines relating to Enzo’s back-story elicited laughs from the

audience I watched the film with, was also the film’s co-producer. As

such, it seems unlikely that he and Argento had a disagreement about

how to portray the character, as with a number of the director’s more

fraught actor relationships, and that this was their intent.

In

combination with Seigner’s involvement, the film thus emerges as

something akin to Argento’s version of Polanski’s Bitter Moon, as

something to be both taken seriously at times and as a self-parody at

others in its commentary on past glories.

How less sympathetic audiences will get the joke is another matter entirely...